It’s undeniable that we are entering a new era of computing. Whether you call it the Internet of Things, the Third Wave, the Fourth Wave, distributed computing, whatever it is, the technology landscape and the machines around us are starting to look different.

Plenty has been written about this shift but one aspect that is often overlooked is how interfaces evolve as we move into new technical eras. An interface, for the purposes of this post, refers to how humans interact with machines. You use different interfaces every day, whether you realize it or not. As the hardware and software that surrounds us change to embrace this new generation, new interfaces will be born.

The Past

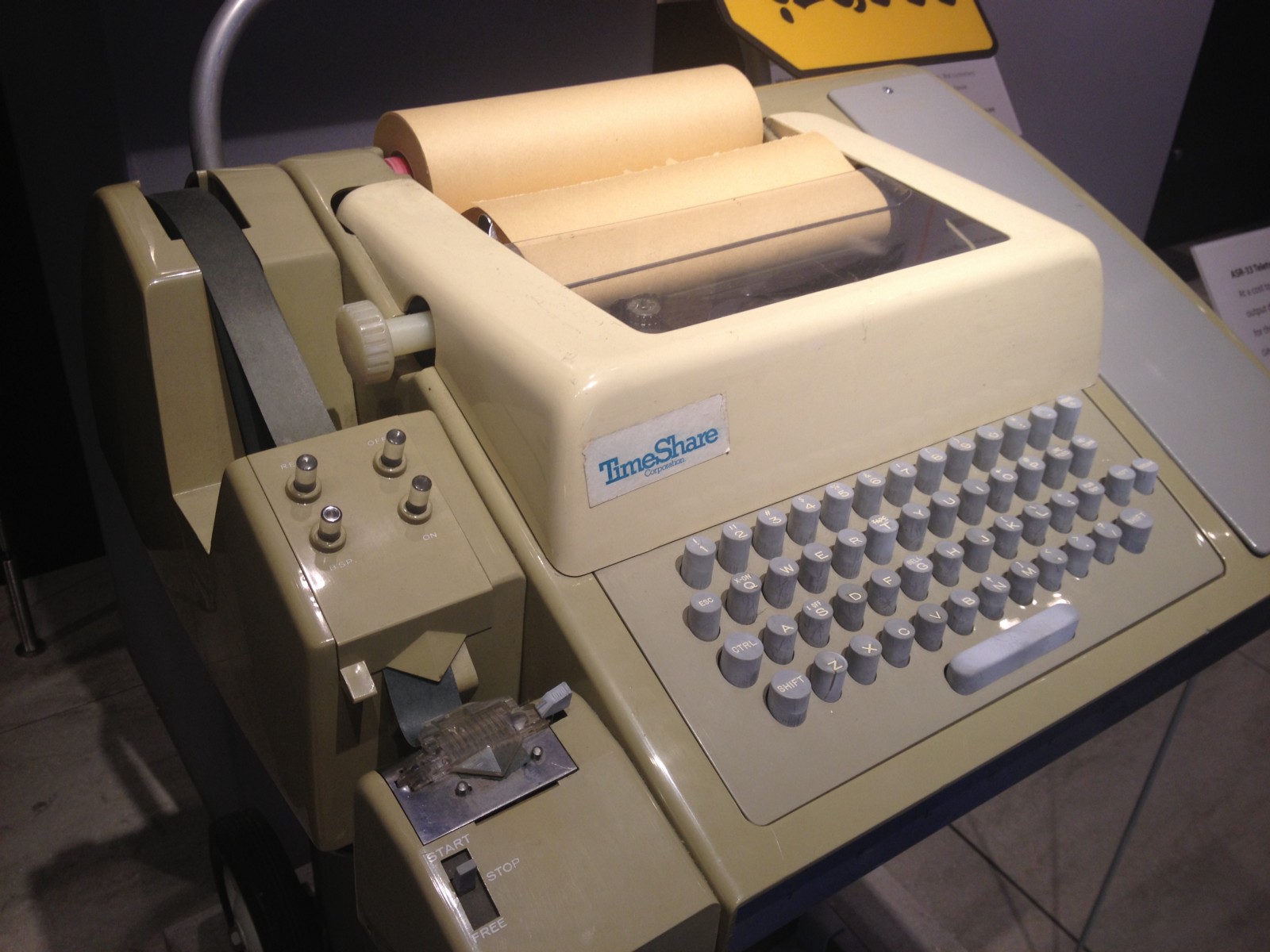

Early computers did not have monitors that displayed the output of the machines. Instead, users would enter commands into a terminal, known as a teletype, and the results would get printed out on paper. Yes, real paper. Eventually, as computers became more mainstream, new interfaces like blinking lights, the monitor, and the mouse were born to allow humans to better interact with machines.

An early interface for computers – a Teletype Model 33

An early interface for computers – a Teletype Model 33

The 1990s brought a new era to the personal computer space, one where actions taken on a machine often depended on the state of a different machine across the network. This era introduced concepts like the World Wide Web and it undoubtedly changed the world of computing as we know it. It also meant that our interface for machines had to change. We needed a way to visualize and easily digest the state of a different machine and, as a result, the web browser was born.

Eventually, we entered the next generation of computing — mobile. This led to a plethora of new interfaces from touch screens to responsive design to fingerprint sensors that allow us to interact with these tiny machines that we carry in our pockets.

The Present

Which brings us to today. We are in a new time. One where devices are more powerful than ever and contain their own application logic. One where there are so many connected things talking to each other that we, as humans, aren’t able to keep track of all of the connections. One where we expect things to “just work together” without any effort and somehow be secure as well. One where connectivity and reliability are (often incorrectly) assumed.

The environment of technology around us is extremely complex. And, like always, the development of the infrastructure has predated the development of our interfaces. There are, however, a handful of different interfaces that are starting to emerge, ready to tackle this massive challenge and become the interfaces of the future.

Voice

Voice is now becoming a commonplace interface thanks to an elegant convergence of several different technologies. Natural language processing is finally starting to understand what we’re trying to say with pretty high accuracy. Text-to-speech algorithms kind of actually sound like humans now and not Microsoft Sam robots. And there are more microphones around us than ever before (this one’s a bit more creepy than elegant I suppose) with mobile phones and Amazon Echos.

As a result of this, virtual assistants are popping up everywhere. The obvious ones are Siri, OK Google (or Hey Google…or Google Assistant…or whatever they call it now), and Alexa (maybe also Cortana, does anyone actually use that?).

There are less obvious virtual assistants too. Bank of America has an assistant, Erica, that lets you interact with your bank account using voice. At this point, we’ve all probably interacted with a phone tree virtual assistant that (supposedly) helps us get in touch with the right customer service representative.

Not every voice interface is a virtual assistant though. Cable TV remotes can now be controlled (with impressive accuracy I have found) with your voice. Identity verification on some banking phone calls can now be done by repeating a phrase with your voice. Turn-by-turn navigation and you car stereo are controlled by voice.

While some of these technologies are still very limited in terms of their function and reliability, they do indicate a trend toward more voice interfaces in the future.

Low-Code

While voice is becoming a great way to interact with a set of partially pre-determined functions, it doesn’t excel when any variability is introduced into the system. You can’t tell Alexa to “run the sprinklers for 15 minutes if it reaches 90 degrees” for example. Even if you could, that would presumably only be because a developer had programmed that “recipe” into the Alexa dialect.

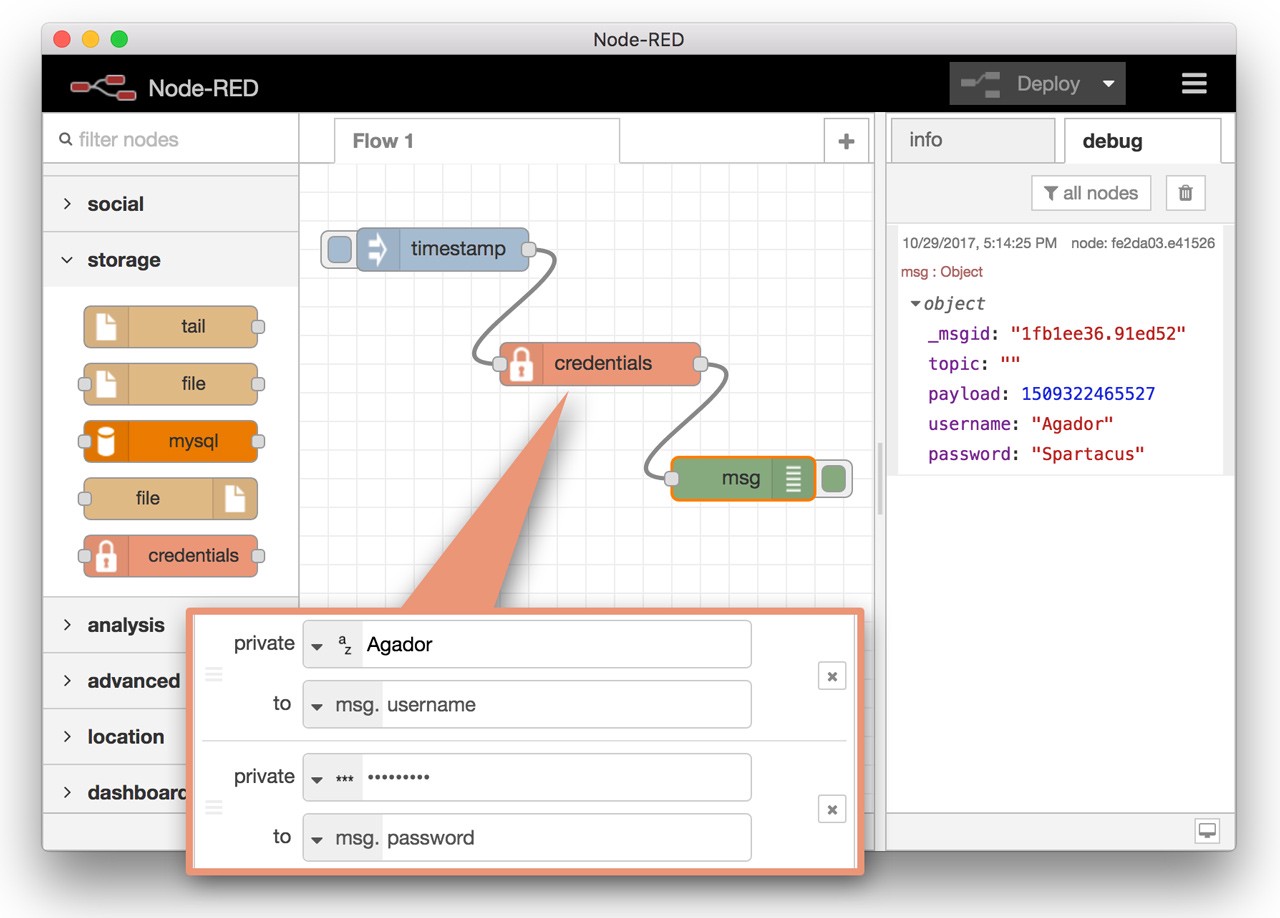

However, users continue to demand more control over their devices. They want to explore and utilize their creativity. They need an interface to do that. And they don’t want to have to write code or know programming to make it happen. We’re seeing control over data and devices expand into a realm of users who are technical but don’t program. This is where low-code or no-code interfaces are starting to shine.

Software solutions like IFTTT and Node-RED allow general consumers and technical hobbyists to connect their different services, apps, and devices together in creative and intelligent ways, all without writing any code. This puts users in control of their own world and not always reliant on what functionality already exists inside of an app or product.

A screenshot from Node-RED — allowing workflows to be built without writing any code

A screenshot from Node-RED — allowing workflows to be built without writing any code

On the enterprise side, products like the niolabs System Designer and Mendix allow companies to define complex applications that power their businesses (disclaimer: I work at niolabs). These tools, which don’t require software developers to operate them, are opening up “intelligence” and “logic” to a much broader audience. This will almost certainly shape the way teams within companies are structured in the future.

Operating early computers meant working in the terminal and understanding various shell commands, something that the layman was not able to do. Eventually, through newer interfaces and better software, computers became accessible to the masses. The same will be true for distributed systems, which are quickly becoming more accessible to non-developers.

Proximity Wireless

While this progress is exciting, many of the newer interfaces don’t seem poised to gracefully handle the immense scale that will come with this new computing era. Launching an app or talking to your virtual assistant to deploy hundreds or thousands of devices is unreasonable. This is where we need devices to do a little bit of self-negotiation and pairing without too much human involvement.

The fundamental idea of this type of interface is if two things are supposed to connect with each other, they are both expecting a connection, and they are close by, then they should just connect. The only human requirement should be to put the system into a “discoverable” or ready-to-pair state.

One of the earliest examples I can think of this is the Wi-Fi Protected Setup feature that exists on most modern wireless routers. According to Wikipedia, this was introduced in 2006. In case you aren’t familiar, the way it works is that in order to join a new wireless network you push a button on the router to automatically connect your device to it within a short period of time. This technology relied on the assumption that if you had physical access to the router then you could probably be trusted.

There are many more wireless-proximity-based interfaces that are in use today. Bluetooth pairing is one that almost everyone has used at this point. Put at least one of the devices in “pairing mode” and another device can connect to it. NFC and close-range RFID allow us to make payments and unlock doors. Even scanning QR codes is a form of “visual” proximity wireless technology.

When talking about large numbers of devices or broad audiences of non-technical users, device interaction will have to be somewhat automatic and not require too much human involvement. The growth of some of these wireless technologies may be an indicator that this interface is just right for that type of problem.

Up until now, humans have interacted with computers one machine at a time. When you type on your keyboard or tap on your phone you are, for the most part, controlling one and only one machine. However, we are quickly becoming in need of interfaces that allow us to interact with systems — multiple devices and machines that work together. It’s difficult to say for sure what these interfaces will be — some combination of the above, voice, low-code, and/or proximity wireless, seem like reasonable expectations at the moment. What’s certain, however, is that they will be novel and different compared to the past.